Matthew Shipp Trio, “Harmonic Disorder” (Thirsty Ear)

My apologies for missing this album’s release date by six weeks; normally I give prompt service to the most important avatars of the avant. And this is another strong dose from pianist Matthew Shipp.

Roots haunted Shipp’s mind when he put together “Harmonic Disorder,” featuring the same trio he tapped for 2007’s “Piano Vortex” -- longtime drummer Whit Dickey and bassist Joe Morris, who’s been augmenting his guitar career with the acoustic four-string for nearly a decade now. Shipp’s relationship to ‘40s bebop inheres mainly via Thelonious Monk, one of the first to break jazz’s harmonic barriers, and Shipp starts the album with the Monkish 6/8 cycling riff of “GNG,” while remaining very much himself in terms of the sloshing rhythm; bebop-style crispness has never been his thing, and though Morris walks and Dickey ticks, they’re not trying to be Wilbur Ware or Art Blakey. Monk surfaces again later in a low range of the piano on the angry “Roe” and on the playful “Light,” where Shipp also bumps into McCoy Tyner and Cecil Taylor. (I know he hates being compared to Taylor, but sometimes, when he hammers the bass or clusters the treble, the comparison applies.)

“There Will Never Be Another You” is barely recognizable from Shipp’s headlong condensation as Dickey sprays the kit Sunny Murray-style; “Someday My Prince Will Come” undergoes an elegant abstractification until it clangs to a nasty conclusion -- one senses that Shipp has finally despaired of the royal arrival.

Carrying the roots theme into Europe, the title cut wanders with a certain troubled, Satie-esque beauty, but this kind of “Harmonic Disorder” isn’t the album’s only attraction; some of the best moments derive from rhythms. The hesitating group conversation of “Orb” (maybe another reference to Thelonious Sphere Monk) demonstrates that even awkwardness can contain its own internal pace. The shoving tension of “Compost,” too, makes a point about the arbitrary nature of a metronome.

Shipp pans into soundtrack territory with the highly visual “Quantum Waves,” where he climbs cobwebbed stairs accompanied by a suspicious bowed bass, and comes to a spooky realization transmitted through low notes that toll like a funeral bell. Two tracks later, the suspense continues with the floating, apprehensive finale, called “When the Curtain Falls on the Jazz Theater.” Dark shadows.

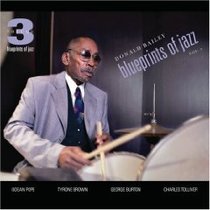

Donald Bailey, “Blueprints of Jazz Vol. 3” (TalkingHouse)

It’s really fun when an album comes out of nowhere and just clicks. Donald Bailey was Jimmy Smith’s main drummer during the organist’s Blue Note prime, so fine, but what’s that you say? He’s brought along extreme saxist Odean Pope and bassist Tyrone Brown, who both wailed so long with Max Roach? And the longest track, a thumpin’ African war dance, features ‘60s New Thing trumpeter Charles Tolliver? And Bailey’s saying things like “I’ve always been drawn to dissonance”? You gotta hear this.

Part of the charm is a family atmosphere that arises from the fact that everybody -- excepting Tolliver but including young pianist George Burton -- hails from Philadelphia. Nobody’s forgotten the formative years John Coltrane spent in Philly, and his ghost is all over this record, from the uptempo “Impressions”-like structure of “Fifth House,” to Bailey’s Elvin Jones-like counter-rhythms on “Family Portrait,” to Pope’s elevational tenor tone and vertical arpeggios on “Plant Life.” Still, the tribute is more oblique than most; this unit approaches Trane with a bluesier, more downtown-rambunctious gait. And whatever Bailey says about dissonance, that aspect of the Coltrane legacy is reflected only in occasional overblown split-tone touches from Pope.

I love every track on this record, but lemme single out a few. The descending chords of “Blues It” make it feel like a relaxed take on Monk’s “Thelonious” as Bailey donk-donks on cowbell. The waltz “Variations” repeatedly squeezes a strangely complicated yet inviting sax riff. When Pope and Brown combine in duo for the standard ballad “For All We Know,” it’s just plain pretty and touching, absolutely real, no trace of nostalgia. Brown makes it sound as if he’s plucking two basses on the tricky riff that precedes “Trilogy,” the African groover where Tolliver gets to show off his softly sour lyricism and bumblebee trilling. Only a heart of granite would fail to vibrate along with the gentle buzzes and slurs of Bailey’s Stevie Wonder-level harmonica work on the lovely “Blue Gardenia.”

The contrast between Burton’s clean, flowing, sometimes moiling piano and Pope’s idiosyncratic looseness gives this record just the right perspective. And Bailey sounds as if he’s been waiting all his life to mix up the beats, boink around his Latin percussion collection and put the hit on that messed-up old trashcan cymbal he holds so dear. The man’s on a ride, and you’re going along.

(The delayed release date for Donald Bailey’s “Blueprints of Jazz” item is Tuesday, March 17, St. Patrick’s Day. Good notes, by the way, from Andrew Gilbert and Scott Yanow.)

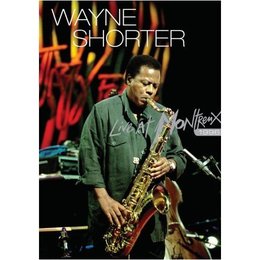

Wayne Shorter, “Live at Montreux 1996” (Eagle Eye DVD)

Few will claim that the great saxist Wayne Shorter ruled the world in the ‘90s. Despite (or maybe because of) the fact that three of the five 1996 Montreux selections presented here hailed from “High Life,” an album that would soon win a Grammy, the music is generic Viagra fusion. The band make the same mistake most festival performers do, trying to pump party juice into an audience that’s perhaps sophisticated enough to appreciate more than chops and energy. Which is no reflection on the talents of drummer Alphonso Johnson, drummer Rodney Holmes, guitarist David Gilmore and keyboardist James Beard -- they kick, and they’re tight, supporting Shorter’s off-peak tenor and soprano. He’s active, but lost.

Fans of vintage ‘60s Shorter may find more to like in the earlier Montreux bonus tracks. In July 1991 (just before the air-crash death of his wife and the September demise of Miles Davis), Shorter warms up to sail freely on his best-known composition, “Footprints,” after surviving a horrible syntho-schlock intro by Herbie Hancock; the band also includes monster bassist Stanley Clarke and drummer Omar Hakim. And the following year finds Shorter reunited with the fabled Miles Davis quintet that created “Nefertiti” (with Wallace Roney standing in for Miles) -- drummer Tony Williams, bassist Ron Carter and Hancock again -- which could never suck. Shorter introduces a somewhat modernized but still impressive “Pinocchio” with an insistent soprano rendition of the theme from “The Mickey Mouse Club,” a statement that can be taken any number of ways, none of them good.

Wayne Shorter is one of jazz’s least knowable genii, and this document does little to turn up the lamp.

Michael Wolff, “Joe’s Strut” (Wrong)

Speaking of the Miles Davis legacy, pianist Michael Wolff (who played with Cannonball Adderley) maintains an obvious affection for ‘50s-‘60s Miles, along with other mainstream jazz of the same period. Wolff’s take is very much his own, and it’s worth hearing.

The Miles hints are plenty. In tribute to Cannonball and Trane, Wolff employs the alto-tenor sax pairing of Steve Wilson and Ian Young. He covers the Frank Loesser stage tune “If I Were a Bell,” a number to which Davis often returned. He covers a song by one Miles godchild (friend Joe Zawinul’s “74 Miles Away”) and writes a song that echoes the work of others (“Joe’s Strut,” which resembles both J.Z.’s “Mercy, Mercy, Mercy” and Herbie Hancock’s “Watermelon Man”). Wolff’s “Wheel of Life” and “The Third You” milk the atmosphere of the 1960s Miles Davis-Wayne Shorter alliance.

But it’s different, because it’s Michael Wolff, a man whose recorded history shows he can absorb any form, from Indian raga to urban blues, and make it sound effortless. Damn, what chops the guy has. Wolff strikes each note on the acoustic keyboard so crisply, gets a tone so rich and shows so much fluid imagination, that you almost pray for him to screw up. In fact, the foot-tapping soul-jazz title tune is my favorite because of its imperfections -- the rhythm is slightly sloppy, communicating a feeling that Wolff is having more fun than usual. And he always seems to be having fun.

Which leads to the only problem one tends to encounter with Wolff: the depth thing. Even at Miles Davis’ prettiest, you hear layers of conflict -- paranoia, anesthesia, hostility, withdrawal, despair. With much ‘50s jazz, you at least hear the basic humanity of a drunk on a barstool. Wolff is always in control. He’s an entertainer who understands what a form can do, and how to achieve that.

So he does it. He gets fine musicians. He records them well. (Drummer Victor Jones’ cymbal sound could be used in recordist college.) So what’s the matter? Nothing. Hell, I’d listen to Michael Wolff anytime.