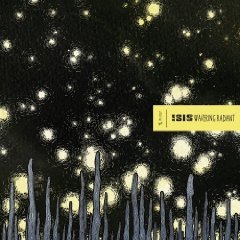

Isis, "Wavering Radiant" (Ipecac)

The resolution keeps getting finer, the musicianship more distinct, the songwriting more thoughtful. The only question is how Isis can continue to grow.

Though the Massachusetts-bred L.A. quintet build their sound on big heaviness, and stake their territory in the vicious battlefields of metal, they (and especially vocalist-guitarist-designer Aaron Turner) present an experience designed for absorption rather than incitement. An Isis album is like a trip to a good museum.

The picture: Isis present themselves beautifully as a unit, the five members complementing one another in color and line. It's an approach that demands individual simplicity, which seems to be their inclination anyway. It works, but it's limiting.

If Isis were a pop group, they'd try to crank out variations of concise song forms, an approach that works for maintaining an audience. If they were a jazz group, they'd maintain a link to their base with complex rhythms, harmonic variations and improvisations. If they were a traditional metal group, instrumental virtuosity and songcraft would keep fans coming back. Ain't none of those. Originality has been Isis' strength. Now that they've refined their sound, though, and spawned quite a few imitators, it's hard to imagine there are a lot of listeners who will require more than five full-length Isis albums.

So if you need only one, it might as well be "Wavering Radiant." It's got all the good stuff. Shimmery yet edgy textures. Flowing and ebbing densities. Dramatic dynamisms. Long, evolving structures. Occasional distant flashes on Jamaican and Arabic models.

And "Radiant" differs in some ways. More than half the songs groove at least partly on triple meters. Cliff Meyer's keyboards push more to the forefront with churchier tones. The repetitions are less obsessive and more adroitly counterpointed. Turner's vocals, both clean and growled, go for more intelligibility and a new grouchy dignity.

Gotta say that the guy most likely to have a 50-year career in music is drummer Aaron Harris. His beats, recorded full and strong, strike with a tom-heavy cleanness, and his counter-rhythms constantly fight banality without ever losing drive. He will continue to evolve, because he has a wide-ranging and curious mind.

If I were to take a wild guess at one album Isis might have been listening to lately, it would be Roxy Music's lavishly produced "Avalon" from 1982 -- a lot of spare, decorative two-string guitar riffs by Turner and Mike Gallagher, and a deep, spacious sound field. Highlights? Normally when taking notes I make check marks next to the best tunes; this time I checked all seven.

It must have felt strange to Isis when, after 11 years together, they got a "best underground" nod at this year's Revolver awards. Their considerable ambitions and hard work have been rewarded with a success they never imagined. If they stop being underground, exactly what would that mean?

* * *

Isis play the Henry Fonda Music Box Theater on Wednesday, June 24.

* * *

I wrote the following story for the final issue of Metal Edge magazine -- at least the final issue under the last incarnation, of which there have been a few over the last 25 years. Since the article appeared back in early April, and the limited number of copies that hit the stands are gone, and it doesn't appear on the mag's obsolete web site, I doubt anyone will mind if I republish it here, with best regards to editor Phil Freeman.

* * *

Isis: Wavering on the Brink

The five artists of Isis tumble your ass with big, slow waves of churning groove and spacious wash; it's no accident that their 2002 breakthrough album was called "Oceanic." Consistent, unified immersion -- that's how their five full-lengths have rolled for over a decade.

But beneath the surface, Isis are a schizoid crew: metallic crunchers devoid of pentagrams; Bostonian gloomsters who migrated to sunny Los Angeles; serious aesthetes who'll giddyup on a mechanical bull; showbiz kids who don't care if anyone knows their names. And damned swell fellas.

Metal Edge collars three priests of Isis in L.A. as they wrap up their new album, "Wavering Radiant," the ultimate refinement of the group's syncopated tribal cycles and psychedelic interbleed. Evading the scalpel are frizz-haired keyboardist-guitarist Bryant Clifford Meyer (Cliff) and moon-faced bassist Jeff Caxide (Ca-sheed; it's Portuguese). Falling as luckless interview victims are guitarist Michael Gallagher, drummer Aaron Harris, and guitarist, vocalist, graphic conceptualist and main songwriter Aaron Turner.

Skinny Turner comes off as an obscure kind of leader. His pants, T-shirt and car are metalman black. His rectangular spectacles, red-streaked beard and polysyllabic speech, on the other hand, say artist. The tattoo on his left arm features not skulls and crosses but birds with matches in their beaks, flying over a picket fence -- "Laying waste to safe and secure residential America," he laughs. Turner rebroke his ankle skateboarding a year ago, and since then gets his exercise running with his two Italian greyhounds, so throw that into the mix. Complicated man, complicated band.

"Part of the reason our music works," says Turner, laying it out with guidebook clarity in a Silver Lake park on a balmy Los Angeles winter day, "is because of the tensions that we have, and the ways that we're pulling in different directions. And it doesn't sound schizophrenic to me, because we all try to make what we do work in the context of Isis."

Prior to the talking, Isis have donned their boho-black trousers for the Metal Edge photo shoot on a hill behind the Hollywood Hills abode of Tool drummer Danny Carey, a band pal. The site is a disused cistern splayed with gang tags; its contents include a couple of Red Stripe empties and an old sneaker. God, what a gorgeous day: on one side, ranks of haze-shrouded palms stretching out to the distant sea; on the other, canyons littered with Mediterranean-tiled homes amid cactus, eucalyptus and pine -- all backdropped by the unforgiving stare of the Hollywood Sign.

Hollywood -- exactly what these five ain't. For one thing, after an eight-to-ten-year association and a solid run of underground godhood, not one of them shows a hint of prima-donna attitude. And as they wait for the snaps, rather than dishing about nightclub revels with Paris Hilton, they're bemoaning the mallification of Glendale and rating the fish burritos at Tere's Mexican Grill, a hole-in-the-wall on an unswanky shank of Melrose Avenue.

"The armpit of L.A.," in fact, is how Harris, sipping java near the Sunset Boulevard Guitar Center the day after the photo shoot, describes the fabled Melrose shopping district a mile west of Tere's. An outdoorsy biker who prefers a Schwinn to a Harley, Harris sports a cheerful disposition and a youthful laugh.

"I'm a pretty angry guy on the inside," he says. "It keeps me going." Harris wants to keep his edge; he says he was just talking to the other guys about Steely Dan and the dangers of sunshine. Becker and Fagen "came out here and started making a bunch of hippie shit," says Harris. "The East Coast is hard. It's hard living, it's hard weather, it's hard people." Most of Isis got acquainted humping boxes in a warehouse of Newbury Comics, an East Coast chain that specializes in underground art and music. Hard was what they knew.

But Turner wanted to Angelize his label, Hydra Head, a boutique outfit that houses the atmospherically noisy likes of Boris, Pelican and Dälek. Another westward lure: the prospect of not freezing. And the dudes had developed a thirst for a change. So in 2003, on the heels of "Oceanic" -- which was released on the West Coast label Ipecac, as have all the group's successive major albums -- Isis became an L.A. band.

Previous visits on tour had not left Harris with a cuddly impression of the city's jaded audiences and laid-back vibe: "I started out fuckin' HATING it, man."

Caxide and Gallagher felt the same -- enough so that after moving west they hauled ass to New York, completing much of the composition on 2006's "In the Absence of Reason" via e-mail. But for the band's sake, the two resettled in L.A.

"I have gotten over the loathing of it," deadpans Gallagher, a red-eyed, bestubbled daytime woodworker who might remind you of the cynical doctor on television's "House." A helicopter bats the clear night sky as we skulk down a residential street around the corner from a Los Feliz dive, the same day Harris spilled. The voice recorder couldn't cope with the bar's jukebox blaring local heroes X ("She had to leave . . . Los Angeles!"), so Gallagher, not one to waste a New York minute, has sucked down the last three-quarters of his Budweiser in about ten seconds, and we're talking outside. Good man.

Gallagher is stoked with the way "Radiant" has progressed from previous recordings, yet he isn't warning old fans of new shocks. "It's very much an Isis record. I don't want to imply that it's more of the same, but we do what we do. We took a little more time, and I think we're playing off of each other better than ever before."

Turner thinks so, too. And time has helped him grow into the strange idea of singing for nobody in a recording studio. "In the beginning I was so uptight about playing things the right way that I would get myself worked up to the point where I couldn't play properly. Becoming more relaxed has allowed me to play better. And that's been especially apparent to me when it comes to doing vocals."

"My groove is just a little more natural," says Harris. "I don't need to think about things as much."

Harris' groove is a big thing with Isis. Turner and Caxide conceived the band's basic formula, but it wasn't till Harris gave it a foundation that they felt they had a real nucleus.

"He's got a great sense of time," says Turner. "A friend of ours remixed one of our tracks a few years ago, and he was asking, 'Did Aaron play to a click track?' And we were, like, 'No.' 'Cause his tempo from the beginning to the end -- which was like an eight-minute song -- was almost perfect."

Although Harris gets a charge from listening to a technical drummer's-drummer such as Bill Bruford, he has no formal training on the kit. He says, however, that tabla lessons a couple of years ago from Aloke Dutta, on the recommendation of Tool's Carey, opened doors. "It engraved in me a better sense of timing, a stronger feeling of music. More than technicality, out of the tabla thing I got a lot of spiritual understanding for rhythm."

Caxide, too, locks into a deep, steady dream world, shifting subtly among his effects pedals -- Isis do enjoy their electronic freakery. Despite the band's unified sound, Turner says it coalesces out of distinct personalities and styles.

Guitarist Gallagher, for instance: "Mike is a very focused player," says Turner. "He doesn't try to just immediately come up with something, he's very contemplative when it comes to writing his parts. Mike is oriented toward space, so he is never interested in creating a really dense part."

How about keyboardist Meyer?

"Cliff is a lot looser," says Turner. "He's much more spontaneous, and as a result his playing is more chaotic. It's not the antithesis of Mike, exactly, but it's a very different approach. Cliff is not a very expressive person, verbally, but he's very expressive in his playing, and I think that that's why music is really important for him."

You hear the chemistry come together live, with Harris' shifting accents adding dimension to the Isis trance. Nodding his head in rhythm, Harris demonstrates how the crowd responds.

"I've watched other bands, and you'll see a few people doing that, but it's really great to see a whole sea of people doing it."

Mostly men; the band's stationary, inward-looking demeanor suggests Isis ain't exactly in this for the chicks. "No," says Harris, "and it's a good thing, 'cause they don't come to see us anyway. Over the last five years there's been a lot more girls, which is great -- not 'cause they're girls, but because it shows that there's a pretty vibe to our music, I guess."

More than most rock bands, Isis have pulled together an audience from various corners of the musical map. Harris says he fears to use the word "metal" when strangers ask what he plays; a lot of cowards shrink from it. Despite making no visual attempt to court the metal sector, Isis chose a name that fits alongside other myth-associated heavy ensembles such as Nile, Marduk, Behemoth or Belphegor, but with a gender twist: "I like the idea," says Turner, "that it defies the typical machismo element that seems to accompany a lot of metal-oriented music."

Behind the drums, Harris gets a kick from scanning a hall to pick out "young people, old people, metalheads, emo-looking, even hip-hop-looking kids." The non-denominational approach obviously appealed to Mike Patton, the wide-ranging musician (Faith No More, Mr. Bungle, Fantômas, Peeping Tom) and label head who signed Isis to his Ipecac imprint. Gallagher credits the connection to the adventure-minded guitarist James Plotkin.

"One of Patton's bands was doing shows with one of Plotkin's projects, maybe Phantomsmasher, and James gave Mike a copy of our first full-length, 'Celestial.' Mike just kind of put it down casually, and James apparently put it back in his hand and said, 'Just listen to it, please.'" Isis pretty much had "Oceanic" together when Patton called to see if they wanted to record for him. Nice timing.

Plotkin, Patton, electronica producer-musician Tim Hecker and Godflesh/Jesu leader Justin Broadrick ranked among the remixers who contributed to the series of vinyl releases that became the wonderfully abstract double-CD Hydra Head release "Oceanic: Remixes/Reinterpretations." Gallagher says the band was able to enlist its first choices of sanctioned saboteurs for the project, except for one who would've enhanced Isis' catholic artview: Tom Waits.

"Me and Aaron Turner are both rabid fans. His music is really strange and beautiful and sad. His whole aesthetic is amazing to me. I've read books about him -- I might be mildly obsessed with Tom Waits. But in a good way."

Isis' austere disc-cover art, poetic narratives ("His head swam with fevered blood, sick with love and laughter") and booklet references to French social philosopher Michel Foucault lend the band an edge of intellectuality. Turner, whose voice switches from flayed screaming to parched melodiousness, writes lyrics that imply rather than state an emotion or a situation; please don't ask him what they "mean." He wasn't a poet before he started versifying for the band, but doesn't mind thinking of the result as poetic. His use of words parallels the wide-ranging attributes of Isis, a goddess of both fertility and death; the first song on "Radiant" is "Hall of the Dead." In reading myths, Turner doesn't relate them so much to the ancient stories and images of Egyptian, Roman or metal gods; he follows psycho-philosopher Carl Jung's way of drawing out the human resonances they represent.

Humans do have their fleshly side, of course. Even if, as Turner says, "We never wanted to be a band that would incite mosh pits," Harris emphasizes, "There's always a heavy physical thing with our music."

Gallagher likes that, and he also likes other art that pulls in more than one direction, such as that of Waits or of Wes Anderson, the filmmaker who directed "Rushmore" and "The Royal Tenenbaums": "I find myself feeling very emotionally involved in his movies and characters, and also laughing like hell at times."

The dual-sided Isis phenomenon has grown, although when the band got together in Boston, they had no particular scheme for world domination. Turner doesn't mind comparisons to Joy Division, Public Image Ltd. and Sleep -- all influential, but none a chartbuster. Harris' description of their success is likely to inspire jealousy.

"It just was all so unexpected. We started out to play music that we wanted to play and not adhere to any rules or guidelines or a certain type of audience. We just wrote some songs, made some records and did some touring," being picked up as openers by the likes of Tool, Neurosis and the Melvins. "All the bands that we've toured with have directly approached us and said, 'Hey, we like your band, do you wanna come on tour with us?' I don't wanna make it sound like it was easy, I think we're just fortunate. We try to return the favor, take on tour a lot of bands that we appreciate and want to expose to our audience, like Dälek, or Jakob, or These Arms Are Snakes."

Even if Isis have scored well enough that they can pretty much live on their musicianly earnings -- 2006's "In the Absence of Truth" hit high on the indie charts, building on the wider visibility they started to achieve with 2004's "Panopticon" -- you probably won't recognize them walking around in the art gallery. On their records, they're credited in small print, in random order, and often with just initials ("B.C. Meyer") for their first names. Isis' photos tend to be shadowy and democratically posed, a slant that carries over into band decisions, which, says Gallagher, are usually carried by unanimous vote -- one exception being the group's participation in a Nike-sponsored documentary, an opportunity they turned down.

Harris says the anonymity is a choice. "We're not a label or a brand. We're not trying to sell a certain image of who we are, other than the music that we play. That's the main focus of this band. I mean, look at us -- we're not very interesting-looking guys. We don't have wild hair or piercings."

"There is so much emphasis placed on the persona of entertainers," says Turner, "that we really wanted to step away from that. Because we don't want to be entertainers."

Anyway, when it comes to posing, Isis are tired of the options. "There's so many bands out there that want to be seen as these dark, moody guys, really intense," says Harris. "And that shit's so played-out, y'know? It's fucking boring, man! You pick up a music magazine, and everybody in there's like, 'Rrrrrr,' with straight faces." Then he thinks about Isis' own shots. "I'm sure that's what we look like!"

Maybe because of the smoky, exotic nature of their sound, Isis have been stamped more than once with the "stoner" insignia. Really, though, that's not a primary focus, even if Turner has been known to recommend lighting up before listening. You might be inclined just to turn off the lights, turn up the volume and get submerged.

"None of us really smoke pot anymore," says Gallagher. "There are some of what I would perceive as little trippy moments in the music, and stuff for kids that smoke a lot of pot and want to listen to it on headphones. But I don't think we're a stoner-rock band."

"There was a period I went through where I smoked a lot of pot," says Turner, "and I felt that was a very good gateway for me -- it allowed me to sink deeper into the music. But I don't need that anymore, and I actually feel like after a while it started to disconnect me, not only from playing music but from a lot of other things."

Not that Isis are gonna go around stumping for abstinence. And although they're serious guys, they do have their lighter moments. Harris mentions a special scene he caught on video camera, which, like your last trip to the bathroom, is now viewable on YouTube. Gallagher tells the story.

"We were in Austria, doing an outdoor festival. We did not go over so well, and we all had that stuck in our heads after the set, sitting around backstage. Earlier, when we had walked around the festival grounds, I had noticed a mechanical bull -- with an American-flag pad! And I put it to everyone that I would cheer them up. So they all followed me there, and I got on the bull, and everyone was very excited afterward. I waited in line about 20 minutes to do it -- I had the longest ride of anyone there!"

Isis have a lot of reasons to be happy. They're cranking out high-quality product all the time -- studio albums, limited-edition live albums, EPs and singles (the music is largely available in vinyl), DVDs, not to mention shirts, posters, beer glasses, a mosquito belt buckle and a "UniPo Tendon Mummy Toy." The design is an outlet for Turner, who, though virtually untrained in music, had some unorthodox schooling at Boston's School of the Museum of Fine Arts.

"I'm a fetishist of objects," he says. "I really enjoy records as objects, and toys and stuff like that. So part of it is purely a materialist thing, which is weird, because that seems sort of out of step with a lot of our other ideas. But at the same time, it's, like, well, those are some of the things that I appreciate about other bands, like when the Melvins did an 8-track tape. But the other aspect of it is that as a designer it gets boring to just be limited to T-shirts. The more stuff we can do in that regard, the more fun it is for me."

Isis are an open-ended outfit. When they experience extracurricular urges, the guys can vent on side projects: Turner with House of Low Culture, Old Man Gloom, Lotus Eaters or Mammifer; Gallagher with MGR; Caxide with Spylacopa; Meyer with Red Sparowes; Harris playing on and recording the new Zozobra record.

Not a bad situation. "I don't take that for granted," says Harris. "I think about that all the time. I don't know why we get away with as much as we do. But I'm glad we do."