Four pianists, eight composers. I sort them into “Why?” and “Ah.”

WHY?

John Cage ranked the Why as equal to the What; his “Music for Amplified Toy Pianos” (1960) was a typical example. He wrote a semi-random score, his purpose relating more to spatial exploration and anti-seriousness. Toy pianos were arranged in a widespread triangle, so the listeners’ ears were constantly trying to locate which player was plinking a few notes or shaking/striking some exotic percussion instrument. As music, it wasn’t much, but as the auditory equivalent of a palate cleanser, it worked. Not too long.

Mel Powell’s “Setting for Two Pianos” (1988) sprayed dissonances around and made us think pianists Vicki Ray and Susan Svrcek were enduring some kind of painful confusion together. I feel like that pretty often, but I don’t think it’s a great subject for music unless Cecil Taylor does it (because he transcends).

For “The Queen of Spain” (1988), Arthur Jarvinen applied a mathematical formula to the pitch intervals of some Scarlatti music and came up with nontraditional tone configurations that could be played on Ray’s and Svrcek’s electronic harpsichords. The result sounded ironic but did not rise to the level of being funny, beautiful or interesting. Conceptual art. My wife’s note: “Edward Gorey meets John Cage and a petulant preschool child.”

Shaun Naidoo’s “Bad Times Coming” (1996) put Ms. Ray in the unusual and difficult position of playing a live duet with a pre-recorded electronic/percussive partner. She was good; the music not so much: Elements of Monkish abstraction, Russian intensity and Arabic hip-hop fought one another to a draw before the composition staggered to its death like a shot elephant.

AH.

Mark Robson played five short pieces written by Henry Cowell between 1914 and 1935. Modernized Mozartism, interior melancholy, dissonant fantasia, swaying colorations and prayerful yearning testified to the range of Cowell’s melodic and emotional genius; when Robson ended by plucking a single low note inside the piano, well, that was satisfying.

Gotta have some “prepared” piano, a form that lends itself to wide-open musings, but not this time, as Ms. Svrcek took on Frederick Leseman’s driving “Nataraja” (1974). The strings were mostly semi-muted to sound like a marimba or kalimba, with a few dedicated to resonant buzzes; the industrious exotica of the composition and its headlong motion made it come off like wound-up gamelan. I felt as if I were meditating in fast-forward.

Where most pastiches thrive on clash, Daniel Lentz’s four-piano “NightBreaker” from 1990 (which closed the program) pulled off the much harder effect of blending disparate material sequentially. Segments of Tchaikovsky fairy dust, Gershwin pomp and Borodin whirl flowed together with artful overlaps, and the sound achieved mass and texture through up to four performers executing passages in unison. Big, yet sensitive and humane.

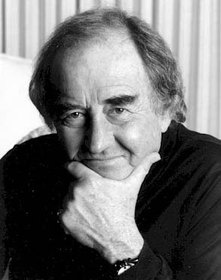

But the deepest moment happened earlier, with just Gloria Cheng at electric piano doing William Kraft’s “Requiescat” (1974). Her face truly grave, Cheng stroked just a note or two at a time, allowing the sonority of each to develop and undulate with the help of electronic effects. She also added flurries of dense high notes by striking the instrument’s sound bars with vibraphone mallets. The music spoke of mourning and near despair, but it also embodied continuation -- an endurance neither willed nor planned. So it was real.

THE PHOTO IS OF WILLIAM KRAFT.