Spirits can possess people. They possessed the great pianist Randy Weston, and he's grateful; we should be too.

The possession doesn't have to be demonic, like the one in Luke 8:27. It can be just accepting the spirits of our ancestors, who live in us whether we acknowledge them or not. Since Weston descends from Africa, it's natural that African spirits would possess him. And through the medium of his surging, corporeal music, we discover that we all descend from the same deep source.

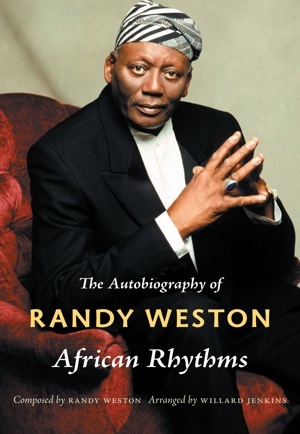

"The Autobiography of Randy Weston: African Rhythms" (Duke University Press) represents a valuable service: Despite the 84-year quest of this artistic (and physical) giant, Americans know him little and understand him less. Much of the reason, the book makes clear, is that he left America behind -- left it for Africa. Without Africa, though, he would have been just another good pianist who admired Thelonious Monk and Duke Ellington.

The African strain ran especially strong through Weston's father, Frank, an admirer of the black-rights advocate Marcus Garvey and an inheritor of the independent blood that drove the senior Weston's self-emancipated progenitors, Jamaica's Maroons. Dad would praise the ancient African civilizations while his young son dodged heroin and ran numbers out of his Brooklyn barber shop, but Randy's biggest break didn't arrive via racetrack profits or knocking around the circa-1950 New York bebop scene with Monk and drum genius Max Roach. Instead, he honed his skills and scored crucial business contacts by playing the resorts in the Berkshires.

The process of early development was quite American. Weston didn't launch his recording career with the ambitious "Uhuru Africa" (1960). His first album, a slate of Cole Porter covers, would sprout in 1954 under the cultivation of producer Orrin Keepnews as the first fleshly session for Riverside Records, which had previously released only waxings of player-piano rolls by Jelly Roll Morton and the like (but would soon sign Monk).

Already 28 at the time, Weston looked like a late bloomer. But unlike teen phenoms such as Bud Powell (dead at 41) or Sonny Rollins (his best work behind him by 40), Weston grew steadily, attaining an elevated plateau around 1990 from which he has not declined. Although he recoiled from the electric piano and unauthorized orchestrations of 1972's "Blue Moses," it remains his biggest seller. His longtime friend and arranger Melba Liston helped make 1973's "Tanjah" a landmark. Several solo recordings, a form at which he excels, kept the flow trickling. Then, under the auspices of Verve Records, Weston undertook a spectacular 1989-98 stint that included three stirring trio albums, the sprawling masterpiece "The Spirits of Our Ancestors" (again with Liston scores), a couple of daring records with Moroccan musicians, and the trance-grooving "Khepera." 2006's trio date "Zep Tepi" is a smilemaker, and I'll talk about the new "The Storyteller" below.

Throughout, while revisiting many of his same baseline compositions, Weston perfected his sense of time suspension and rhythmic magic, especially effective in the company of Afro-savvy hand drummers such as Big Black, Chief Bey, Neil Clarke, and his son, Azzedin Weston. He feels that the magic evolved from Africa, where he lived on and off for many years -- he speaks of being called by Isis, of being drawn into the healing trances of Moroccan Gnawa musicians, of a local woman's vision locating a stolen motorcycle. The magic was aboriginal: Like the writers Paul Bowles and Allen Ginsberg, to whom he wasn't much drawn, Weston settled in Tangier in part because its varied history and seaport location made it an open crossroads undominated by orthodox Islam; pre-Muslim spirits and traditions lived on in the culture and in the transcendent sounds of despised locals such as the Gnawa.

Weston is an idealist. He believes that African rhythms have the power to inspire and unite, and his desire to spread the word has impelled him beyond his keyboard into the realms of culture-center creation, nightclub entrepreneurship and festival promotion. As a businessman, he has sucked. And his dedicated Afrocentrism has hung like a millstone around his commercial career, subjecting him to the same kind of discrimination Pharoah Sanders and Archie Shepp suffered -- although Weston admits that he valued 1960s "free jazz" almost as little as he did the Beatles.

Still, Weston harbors few regrets, and considering his artistic hospitality and the incredible moments he's experienced around the world -- breaking ground to perform in both a primordial Japanese temple and a Canterbury Cathedral crypt, for instance -- you can see why. In some places, especially Africa, he's revered as almost a god. For his own part, he sees his art mainly as that of a storyteller. In the so-called Dark Continent, that's called a griot.

Telling his life story bookwise, Weston relies on basic speech patterns and a good memory; this memoir is not intended as literature. Co-author Willard Jenkins has served well in organizing the narrative and interspersing comment from key witnesses, but in common with nearly every new book I've read in the last couple of decades, this one couldn't afford the luxury of an editor -- redundancies and superfluities abound.

Which doesn't negate the wonder of the journey or the importance of the artist. No jazz fan should neglect Randy Weston.

* * *

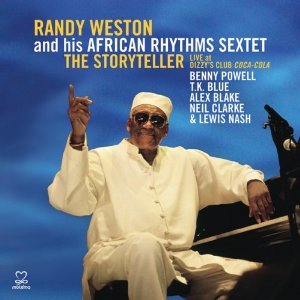

Not coincidentally, "The Storyteller" (Motema Music) is the title of the latest live recording by Randy Weston and His African Rhythms Sextet. Late as it arrives in Weston's catalog, it serves as an excellent introduction to his music: The man has never stopped growing.

Weston builds his pyramid on a solid base: longtime bandmates Neil Clarke on hand drums, Alex Blake on bass, T.K. Blue (Talib Kebwe) on sax & flute, and Benny Powell (who died this year) on trombone, plus a veteran new conscript, Lewis Nash, on traps. Settling into late friend Dizzy Gillespie's Club Coca-Cola in New York last year, these wizards stir a stew full of savory lumps, blended just right.

A sympathetic musical impression of Africa is instantly recognizable; it has something to do with warmth, tactility, breathing, camaraderie and the kind of gently diffused sunset that appears on the back of the CD cover. The rhythms can be generated using just two hands, but when you've got 12 hands and some mouths and feet, the easy stretches and compressions of time combine to put your body and mind in a place of no pain.

The record begins with Weston prodding the piano alone like a lazy baby elephant, rousing himself to dissonant morning odors before the whole band kicks into the humid communal Afro-Caribbean bump (with bop trimmings!) of "African Sunrise." The title "Jus' Blues" is a jest, as we discover at length the Moroccan motivations an urban indigo can suggest. Likewise, when the Weston crew extrapolate on his early Monkwise nugget "Wig Loose" and his jumpy Latinate hit "Hi Fly," the original tunes are more felt than heard; they're curtains drawn back before the altar. Mingus and Ellington drop by for the ride, and the rhythm train sure knows where everybody's going together -- the motherland, brother.

If you're wondering whether it's possible to give and get pure joy at the age of 80-something, the answer's right here.