Gary Peterson had two baseball bats. The swat sticks were old and he was 12, so they must have been his father's, or his grandfather's, or Moses'.

Normally, people tell you to take care of your things, but that's not always best. No one had taken care of these bats. They had been left out in the weather forever, a neglect Gary perpetuated in rainy Western Washington. The now-unvarnished bats had grown gray, showing the kind of smooth surface cracks that indicate strength rather than weakness. In winter they even showed a tinge of green moss. You could hit rocks without leaving dents in the wood, and we did hit rocks, as well as whiffle balls, golf balls and tennis balls. Baseballs cost too much, so we didn't hit those much.

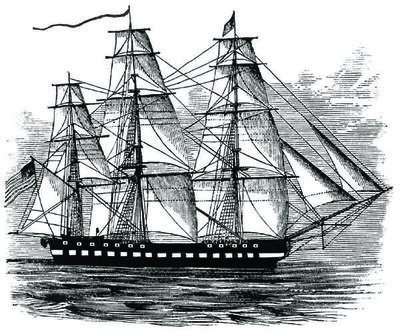

The bat barrels retained no trace of the trademark labels that were burned into most every product -- Louisville Slugger or Adirondack for instance. They were just old wood, the kind I imagined when I read about the USS Constitution a.k.a. Old Ironsides, a legendary war frigate built in 1897 off whose oaken hull cannonballs were said to bounce harmlessly. Oak is not the usual material for baseball bats; the standards are supple maple and lightweight ash. But Gary's bats felt like oak.

One bat, made for hitting home runs, had a fat barrel and a narrow handle. The other had a handle almost as thick as the barrel, so you could hit singles off any part of it. Both were great bats.

With these bats in mind, I resolved at 13 to make one for myself. We lived in a boxy housing development at the edge of a new-growth forest, every tree of which would soon be cut down for further suburban expansion. Some of the land had previously been cleared for farms, evidenced by a couple of dilapidated cabins still leaning out in the leafy gloom, but a few tall burned pine-tree remnants suggested that an ancient forest had succumbed to a modern fire.

Most of the newer replacement trees were poplars and birches. Bats could be made from birch. And some of the local birches looked the right size for a bat. So I took a handsaw into the forest.

A young tree full of sap is not easy to saw. I got blisters. But I brought a suitable length back to our tool shed and stripped the pale birch bark, which was backed with green and left the white wood slippery.

Then I learned bat wood is supposed to be dried and aged. Huh. Since I knew great bats should be left in the rain, drying ran counter to my experience. And I did not want to hear about aging. How long? A week? Two? Beyond that, you had to be joking: Baseball season loomed.

I laid the untooled staff on a heat register and looked at it every day. Nothing happened, except it was getting bowed. Could I hit with a curved bat? Maybe. Was it dry enough? Wait, it cracked four inches lengthwise, then cracked some more. Could I hit with a curved, cracked bat? I was a weak hitter even sans handicaps. With great sorrow, I capitulated.

Like stone idols, Gary's bats may still exist. My stick might too, charred beneath the ground. Relics can become such without intent. Even as firewood, my bat was a bust.